Economy has never been an attribute of the photographic process, even in the analogue era of film cartridges and emulsion prints. Ernest Cole, like many photographers, took far more photographs than was needed – far more than the 183 images used in his landmark photobook, ‘House of Bondage’ (1967). There is nothing exceptional in this, but given the legendary status of Cole’s book, first published in New York in 1967 using prints and negatives smuggled out of apartheid South Africa, the opportunity to gain a fuller view of what he saw and photographed in the early 1960s is a rare privilege.

For decades, Cole’s identity was synonymous with ‘House of Bondage’, but the 2017 discovery of a huge cache of his negatives in a Swedish bank and retrieval of original handprints from various European archives has enabled a more expansive view of his legacy. For purposes of this essay, I will stay with ‘House of Bondage’. Celebrated, banned, illicitly distributed, creatively hijacked, falteringly recovered, and lavishly updated in a new 2022 edition, Coles’ book deserves the various plaudits bestowed on it. ‘House of Bondage’ is not just a photobook – it was an incendiary device, a blatantly unapologetic study of apartheid’s vile mechanics and effects on ordinary black South Africans.

The extraordinary journey of this book from idea to actuality – an agit-prop sociological account of black life in apartheid South Africa – is now well known. I do not intend to revisit the work of Joseph Lelyveld (a New York Times journalist and frequent collaborator with Cole in earlier 1960s Johannesburg), Ivor Powell, Gunilla Knape and Darren Newbury. Read their work, as well as and Cole’s 1968 Ebony magazine essay “My Country, My Hell!”. Rather, what I want to highlight here is the role of time in appreciating Cole’s photographs, and the book they refer to.

‘House of Bondage’ straddles two temporalities: a lapsed past and haunted present. These timeframes are locked in a deep embrace. While patently a statement on past humiliations, the book continues to be received as a mirror to contemporary failures. Its urgencies are undiminished, even as its component parts, the individual photographs that weighed and measured a fascistic, race-based system, have become decoupled from the book that originally housed them.

Twenty-seven of the 35 vintage prints in the Cape Town leg of the Goodman Gallery’s multi-city tour of Cole’s work do not appear in the original hardcover edition of ‘House of Bondage’. Many of the prints however directly relate, in time and geography, to frames appearing in the book’s 14 illustrated chapters.

The photograph of a bride being chauffeured in a rented American convertible offers a different angle on the same animated moment recorded on page 172, in a chapter about middle class black life. The destitute women hawking fruit outside Denneboom railway station, near where Cole was born on the eastern outskirts of Pretoria in 1940, is pictured in a more energetic pose on page 90. The four passive youths gathered around an architectural pillar in Pretoria’s CBD are from the same gang of pickpockets that Cole describes at work outside the Eastern Silk Bazaar on page 135.

Other works in the exhibition are harder to locate, like some of the unseen prints from his exploration of religion and various photos of mine labourers being processed for work, showering and at grim leisure. Some of these photos were made at the “barracks-like buildings” of Rand Leases used to house miners. These photos were clearly jettisoned in the editing process. This happens.

Cole worked on his book project with concentrated focus from at least 1963, when he spent 26 days in Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto. The experience suggested a new area of focus he states in the chapter titled “Hospital Care”. The six young men, two with bandaged eyes, another with his arm in a sling, in one of unseen prints are likely inmates of Baragwanath. A motorbike accident led to Cole’s hospitalisation.

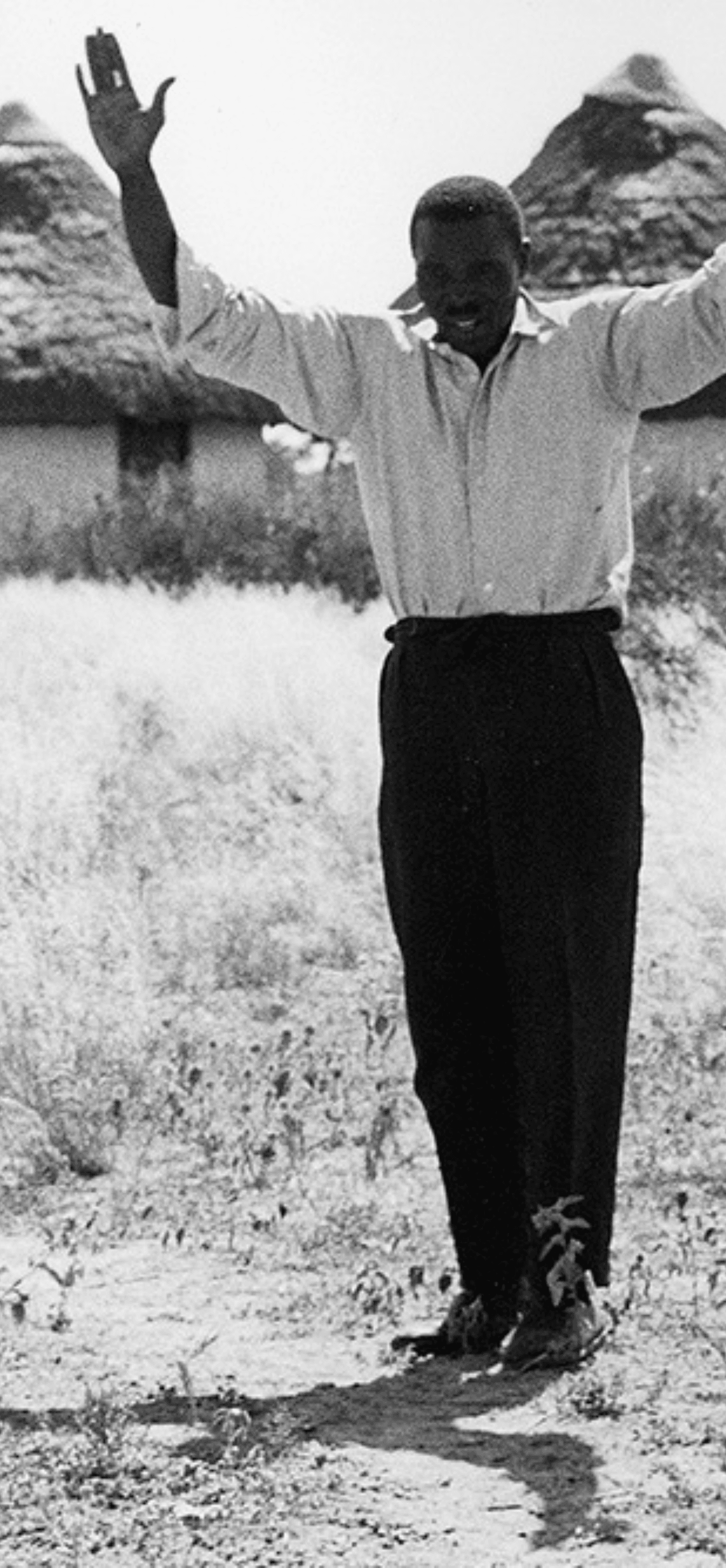

Cole rode a Lambretta scooter. This detail signifies – but what exactly? Cole formed part of a burgeoning avant-garde, a hip young set that included journalist and poet Keorapetse Kgositsile. Cole later approached Kgositsile in New York to write the introduction to ‘House of Bondage’. The book’s publisher went with Lelyveld. It was one of many compromises that his finished book presented. Cole was also friendly with Pretoria jazzmen Philip Tabane and Julian Bahula. Cole documented their band, The Malombo Jazz Men, practicing and performing. The 2022 edition of ‘House of Bondage’ includes a new chapter titled “Black Ingenuity” featuring some of this work interspersed with photos of boxers, painters and other musicians.

But the scooter also points to other possibilities. David Goldblatt used a BMW600 motorcycle during the making of his celebrated photobook ‘In Boksburg’ (1982). “The logistics of the photographer in the field are interesting,” Goldblatt told me in 2013, “and they are a vital clue often to the way the photographs were conceived and made. To me the means of getting to a place are absolutely primary; they are as primary the camera itself.” The mostly unseen Cole photos attest to Cole’s roaming method as a photographer, his wandering from railway stations and mine compounds to urban peripheries amenable to outdoor religious ceremonies. In 1964 Cole even visited Frenchdale, a far-flung gulag in the Northern Cape where apartheid dissidents were banished. He drove there “in my well-used Volkswagen,” he tells in ‘House of Bondage’.

In broad overview, Cole’s photographs in ‘House of Bondage’ visualise the hopelessness and misery that confronted black South Africans living in the urban centres of Johannesburg and Pretoria circa the early 1960s. His photos show crowded train commutes, brutal work circumstances, predatory credit systems, atomised family relations, impoverished schools, youth delinquency, police harassment and bullying municipal signage. The dominant rhetorical mode is documentary witnessing informed by his photojournalism. Purposefully grouped and variously scaled for effect, Cole’s 183 photos in House of Bondage visualise what he, in the first chapter, describes as the “extraordinary experience to live as though life were a punishment for being black”.

The rhetorical strategies used to present Cole’s photos – full-bleed layouts, dramatic juxtapositions, strong image-text relationships – represent an outmoded approach to photobook design. This criticism misses a larger point. The book was provocation. “I knew that I could be killed merely for gathering the material for such a book and I knew that when I finished, I would have to leave my country in order to have the book published,” Cole wrote in ‘Ebony’.

Appearing in the same year as celebrated Johannesburg photographer Sam Haskin’s graphically inventive but stereotypical ‘African Image’, Cole’s book punctured the tropes of primitivism, pictorialism and ethnography that had for too long rendered black subjects as imaginative props for white photographers. In this alone his book represented an ambiguous first. Here was a black South African providing the duplicitous western world – which decried and boycotted South Africa, while actively treating it as an ideological ally and trading partner –with a front-row seat to the ugly theater of oppression. His images hit like gut punches, as intended.

“The silence which effectively walls in the life of the Negro in South Africa has been broken,” wrote Edward A. Weeks, editor emeritus of The Atlantic magazine, in a review, “and the window it provides for us is a shocking one.” The New York Times punted Cole’s book with a two-page spread, while literary exile Daniel Pule Kunene reviewed the book for the Los Angeles Times. “Anyone who looks into the book will at once be aware of the photographer’s lack of sentimentality, his tenderness, his anger, his wit,” wrote Dan Jacobson, another literary exile, in The Guardian when Cole’s book was published in the United Kingdom in 1968. “Deprivation and discrimination are shown to us for what they are.”

Cole’s photos tore down the genteel façade of a brutal and technocratic system. It prompted a reckoning. ‘House of Bondage’ was banned in South Africa in May 1968. The fear Cole’s book instilled in the apartheid state is explicable. “Apartheid was both constructed and opposed in visual terms,” argues Newbury. Okwui Enwezor, writing in the book for his exhibition ‘Rise and Fall of Apartheid’ (2013), makes a similar point. He states that Cole’s images “demonstrate the central position that photography would play in documenting, as well as undoing, apartheid.”

The prohibition of distribution of Cole’s book in South Africa, while a blow, was matched by an even greater cruelty. Declared persona non grata, Cole’s application to renew his passport was denied in September 1968, leaving him stateless and stranded in New York. He continued working, enthusiastically at first, in his wandering manner, frequently deriving insight from the street, but America – then as now – was no paragon of non-racialism. Even, to misquote Prince, for a photographer loved by all the critics in New York.

The pain of exile, his removal from family and friends, also exerted its toll. Cole gradually faded from view. “Cole has disappeared from the world of professional photojournalism,” wrote artist Alan Sekula, an admirer of Cole’s work, in 1986. Like the poets Bessie Head and Arthur Nortje, who used their craft to describe the existential confinement and drumming rage of millions, Cole died in exile, in a New York hospital in 1990, just as the apartheid regime began to collapse. He had published just one book.

The original edition of ‘House of Bondage’ is today rightly celebrated as a masterstroke. Included in Martin Parr and Gerry Badger’s The Photobook: A History (2004-14), it is described as both “a sociological document” and “a polemic.” Photo historian Darren Newbury in 2013 characterised ‘House of Bondage’ as “one of the most significant landmarks in South African photography” and “a classic of the documentary genre.” These appraisals extended and built on the recovery of Cole’s work that started in the 1990s.

‘From Margins to Mainstream: Lost South African Photographers’ (1994) marked the first known instance of Cole’s photos being exhibited in South Africa. Curated by activist Gordon Metz, the travelling exhibition brought together six early practitioners of social documentary photograph: Cole, Willie de Klerk, Bob Gosani, Ranjith Kally, Leon Levson and Eli Weinberg. A similar sense of co-operative meaning and collective recovery marks Cole’s appearance in the permanent displays at the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg. Cole’s photographs form part of an extensive archive of photographic material used to inform and animate the histories told within this private museum.

“Are we really ready to announce the end of apartheid?” wondered writer and actor John Matshikiza in a 2001 newspaper editorial following a visit to the newly opened museum. “Are we confident enough to encapsulate it as a piece of dead history and turn it into a museum piece, as distant as the mummified remains of Egypt, Greece and Rome?” Matshikiza suspended his jovial and practiced cynicism in front of Cole’s photography. “Each of Cole’s startling black-and-white images carries the power of a carefully judged painting telling the whole truth, in all its bitterness, but invested with a certain spiritual beauty,” writes Matshikiza. “Here, at last, we come to grips with what apartheid really meant—the numbing, humdrum horror of a black person’s daily existence.”

It is a recognisable humdrum adds Matshikiza. “The apartheid notices have come down, but black life is not much different from the images that strike at you out of Cole’s photographs,” he writes. “Hopeless poverty and hopeless disease still walk hand-in-hand. Black maids and nannies still sit in hopeless contemplation in the same servants’ quarters up in the sky, or out back, near the drains and the dog kennels. On Sundays they still pray for pie in the sky.” Matshikiza’s brief but incisive review anticipated further, sometimes equally truncated, but no less meaningful, encounters with Cole’s photography by South Africans.

They include Powell, Colin Richards (in a catalogue essay for ‘Rise and Fall of Apartheid’) and, most recently, photographer Lindokuhle Sobekwa. “As a ‘born free’ who grew up after the end of apartheid, I can still connect and relate to his work and experience,” wrote Sobekwa in a 2021 essay about a Cole photograph portraying an overcrowded train carriage. “We were both black children growing up in the townships. Conditions may have since changed – but not enough.” Not enough. Take a look at contemporary South Africa. Cole’s work might portray a drowned world, but it remains fissile matter, in large part because it suggests no easy reconciliation between then and now. The house of bondage endures.

Sean O’Toole is a writer, editor and occasional curator based in Cape Town. He has published two books and edited three collections of essays.